Women in Wine

If you have been following our social media channels, you will have seen that we have been running training sessions for our team via zoom during lockdown. For my latest session, I was asked to focus on women in wine.

Hopefully one day, the fact that a certain wine was made by a woman winemaker won’t have to be a talking point, it is not a novelty or a privilege, but just a fact. Of course women make wine, of course women make great wines. But the sad fact is that throughout history, women have been discouraged or forced out of wine. Wine has often been synonymous with privileged men and the focus on women has generally been on the negative connotations of alcohol; women depicted as slovenly drunks, the perception of promiscuity, the fear of adultery etc. Yes, times have changed and there are more women in wine than ever before, but we’re still not there yet. The world of wine, unfortunately, is not the most diverse place, not just from a gender point of view, but also racially and economically.

Focussing, for now, on gender, let’s take a look at the history of women in wine, or rather, the lack thereof. For my research on this, I found Women of Wine: The Rise of Women in the Global Wine Industry by Ann Matasar very useful and would wholeheartedly recommend.

Going back as far as Ancient Egypt, we can see the difference afforded to men and women with regards to wine. Upper-class Egyptian men would have jars of wine placed in their tombs after they die to allow them to be able to enjoy life after death. The wealthier the man, the more wine they would have in their tomb, wine was found in the tomb of King Tutankhamun (even though he was only a teenager). Women, however, were not allowed wine in their tombs, for fear that they would get drunk and act in a promiscuous fashion in the afterlife.

The ancient Greeks were the first to establish a male-only drinking club, called a Symposia. During these clubs, wealthy men would convene to drink wine, women were allowed in but only to serve the wine or as prostitutes.

In early Roman times women were not permitted to drink for fear it would cause inappropriate behaviour. If a woman was suspected of drinking, a man could kiss her on the lips to see if he could taste the wine on her. Women were to be sentenced to death if found to be drinking. In the times of Romulus for example, it was recorded that a Roman girl who stole the keys to the wine cellar and got drunk was starved to death. Another was killed by her husband by being hit with a stick until death. These severe restrictions did lift to the point that Livia, the wife of the first Roman emperor Augustus, was said to have reached a very old age thanks to her favourite wine, the Pucinum. The Roman drinking clubs were known as Convivia and centred on food, drink and camaraderie and were, of course, male only.

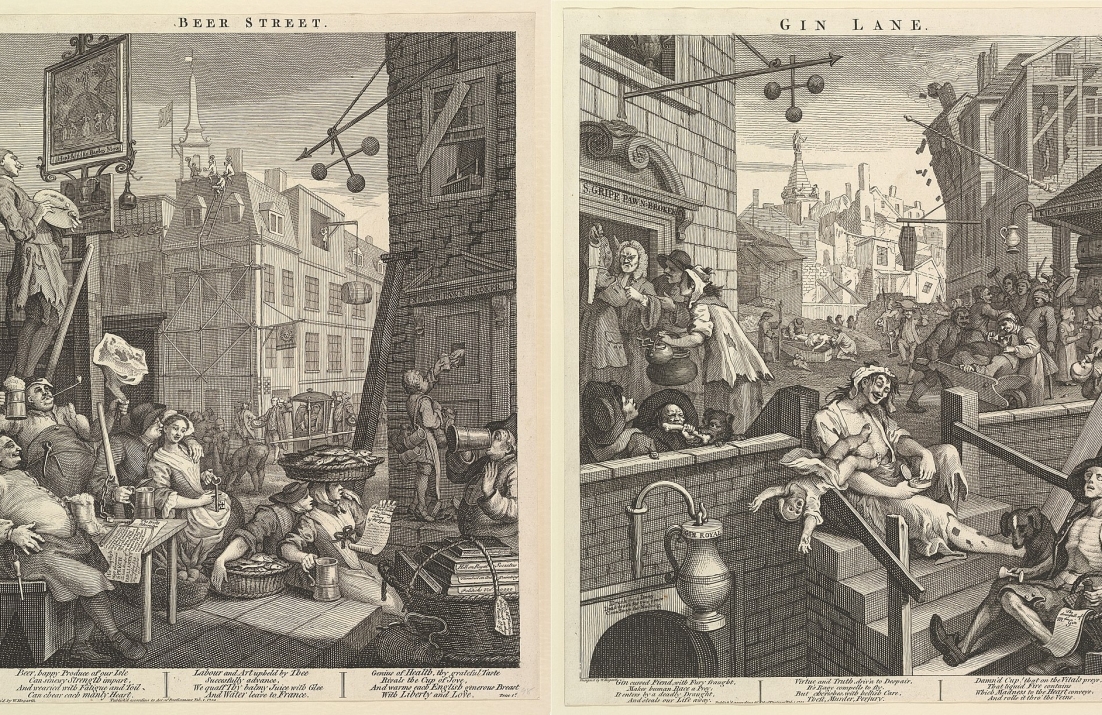

These prejudices around women and alcohol continued through the ages, and some are still referenced today. Looking back to the gin craze of the eighteenth century, people still think of the famous picture ‘Gin Lane’ by William Hogarth and the term ‘Mothers ruin’. Of course, it was not just women drinking gin during this time, but that is the image that has prevailed throughout history.

In 1689, King William III of Orange overthrew James II of England and became the King of England. The following year King William passed the ‘Distillers Act’, subsequently allowing the public to produce alcohol for free in their own home providing they passed a 10-day public notice. In 1720, the mutiny act was passed which stated that anyone who was distilling alcohol wouldn’t have to house soldiers in their home. These factors caused an enormous rise in local gin production, so much so that by 1730 the number of gin shops in London exceeded 7000 (approximately one in every three houses). By 1733, the average person was drinking 64 litres of gin a year, approx. 1.3 litres of gin per week at approx. 160 proof! Turpentine and sulphuric acid were common additions to the ‘gin’. For many working-class Londoners, gin became more than a drink, it was an escape from their brutal day to day lives; it was very cheap, it eased hunger pangs and relief from the cold. One tragic event which sprung the government into action to address this, was the case of Judith Dufour who strangled her child to sell their clothes for gin, hence the term ‘mothers ruin’. However, that tragic event shows a snapshot of the gin craze of the eighteenth century and the impact of alcohol on not just women, but the lives of the poor in general. Mother’s ruin, yes. But not exclusively.

Beer Street and Gin Lane

Looking at more modern times and the wine trade, one of the biggest barriers for women to overcome has been the lack of access to work. In the cellar, there had long been the assumption that women were ‘too weak’ to do the physical aspect of the job, be that moving the barrels, rack and return, or working with other winery equipment. Incredibly, superstition has also played a part in barring women from wineries, with some people believing that women’s menstrual cycles could have an impact on the fermenting wine. The assumption being that if a woman was menstruating it would cause the wine to turn to vinegar or re-ferment monthly! In Ann Matasar’s book she interviewed a winemaker who said, “When I started, there wasn’t a field more sexist than vine-growing and oenology! At that time, it was said that a woman shouldn’t get into a wine cellar, because if she did, her ‘petticoat’ would make the wine turn sour.”

Of course, throughout history there have been women who have ripped up the rule book.

Veuve Clicqout was the first woman to run a Champagne house after she was widowed at age 27 (Veuve is the French word for widow), not only did she successfully run the Champagne house in a time when women were brought up to only be wives and mothers, but she also created a pink champagne by blending a proportion of red wine into the champagne which is a process still used and unique to the region in the EU, she also invented the riddling process which is a key part in the production of Champagne (and still used to this day, albeit mostly now mechanised). Other notable women in wine include Dona Antónia Adelaide Ferreira who is credited with improving the quality of Portuguese wines in the 1800s, Louise Pommery who created the ‘Brut’ style for Queen Victoria which proved to be a massive hit with the British public, Lily Bollinger who not only kept her winery running through Nazi occupation but after the war achieved royal awards for her Champagne, Isabelle Simi who was the first female winemaker in the USA and managed to keep her winery afloat during prohibition when most wineries around her folded and Sarah Morphew Stephen who became the first female Master of Wine in 1970.

Portrait of Madame Clicquot Ponsardin (1777-1866)

Here at Ellis, we have a number of wines made by women, and Colombini’s Casato Prime Donne winery is run entirely by women, a unique case in the whole of Italy:

- Donatella Cinelli Colombini, Montalcino, Italy: winemaker Valerie Lavigne

- Dominio de Punctum, La Mancha: winemaker Ruth Fernandez

- Domaine N & G Fevre, Chablis: winemaker Natalie Fevre

- Domaine Michelot, Nuits St Georges: winemaker Elodie Michelot

- Domaine Marc Morey, Chassagne Montrachet: winemaker Sabine Mollard

- Domaine Pascal, Puligny Montrachet: winemaker Alexandra Pascal

- Domaine Gour de Chaule, Gigondas: winemaker Stephanie Fumoso

(she heads the organisation of female winemakers in the Rhone ‘Femmes Vignes Rhone’) - Domaine Morin Langaran, Picpoul de Pinet: winemaker Caroline Morin

- Les Vignobles Foncalieu, Languedoc: winemaker Mélanie Loustalet

- Hacienda el Ternero, Rioja Alta: winemaker Itziar López Casado

- Finca Sophenia, Mendoza, Argentina: winemaker Julia Halupzcok

- Backsberg Estate, Paarl, S.Africa: winemaker Alicia Rechner

- Schubert Vineyards, Martinborough, NZ: winemaker Marion Deimling

- Azienda Agricola Crociani, Montepulciano, Italy: winemaker Susanna Crociani

- Musita, Sicily, Italy: winemaker Carmela Ardagna

- Bodegas Taron, Rioja, Spain: winemaker Laura Manzanos

- Cake, Adelaide Hills, Australia: winemaker Sarah Burvill

Just a quick glance at this list of talented winemakers shows how wrong history was. Women ‘too weak’ to be winemakers? I think not.

Megan Clarke, Wine Buyer

Follow her on Instagram: @megs.world.of.wine